Understanding how light regulates circadian rhythms gives us powerful tools to optimize health, boost productivity, and improve sleep.

Let’s explore how light affects:

- Melatonin

- Serotonin

- Cortisol

—three hormones tightly linked to circadian function—and how we can use smart lighting solutions to live in harmony with our body’s natural clock.

Light’s Effect on Melatonin Production and Sleep

Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland in response to darkness, which in nature correlates with the decline in blue light following sunset. Melatonin helps regulate the timing of sleep by signaling to the body that it’s time to wind down for the evening. Exposure to blue light, particularly in the 460–480 nm wavelength range, either naturally during the day or artificially at night, suppresses melatonin secretion and delays sleep onset (Brainard et al. 2001).

The amount of blue light we are exposed to prior to bed can have a surprisingly powerful effect on our sleep. Electronic screens (cell phones, computers, TVs, etc.) and overhead LED lighting emit blue-enriched light, which at night (ALAN) can delay sleep and reduce deep, restorative stages (Chang et al. 2015). Reduced sleep quality has been linked to increased risk in a wide range of disorders including depression, obesity, and impaired immune function (Grandner 2022).

To counteract the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) or blue light at night (BLAN), avoid bright lighting and screens at least one hour before bed. Instead, opt for amber or red-spectrum light, which has minimal impact on melatonin suppression and helps promote relaxation (Figueiro et al. 2011). These lights are best used in our bedrooms and areas we commonly relax.

Blue Light’s Effect on Mental Health

While blue light at night can certainly be detrimental to your sleep cycle, during the daytime it can be massively beneficial to your mental health. In the daytime, exposure to blue light stimulates the production of serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, cognition, and energy levels (LeGates et al. 2014). It also helps regulate cortisol, a hormone critical for alertness and stress response, which follows a diurnal pattern—peaking in the morning and declining toward evening (O’Byrne et al. 2021).

Inadequate daylight exposure can cause a form of depression caused by disrupted circadian timing. Such conditions can be induced by many common situations:

- Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) – Spending significant time in reduced-daylight, more extreme latitudes in Winter.

- Indoor Affective Disorder (IAD) – Spending significand time indoors under standard electric lighting due to work, lifestyle, climate or weather.

Without access to sufficient blue-sky melanopic light during the day to set and maintain natural circadian rhythms, the health of mind and body are at risk. Light therapy using intensely bright, blue-enriched light has been shown to significantly alleviate symptoms of SAD (Lam et al., 2006) although less harsh ‘therapies’ using more natural sky-blue-enhanced circadian lighting in the home and office is now available to bolster circadian function.

Even in those without SAD or IAD, greater exposure to daytime light is linked to better mood, lower fatigue, and improved sleep outcomes. Scientific and medical consensus recommendations (Brown et al. 2022) for melanopic light levels (called m-EDI and measured in lux) to maintain healthy circadian function are:

- >250 m-EDI during daytime

- <10 m-EDI during evening

- <1 m-EDI for sleep at night

How Blue Light Increases Focus, Alertness, and Productivity

Blue light exposure during waking hours enhances alertness and cognitive function by stimulating melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells, which signal the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)—our central circadian pacemaker (Lockley et al. 2006) to regulate our hormones and metabolism (Buijs et al. 2003).

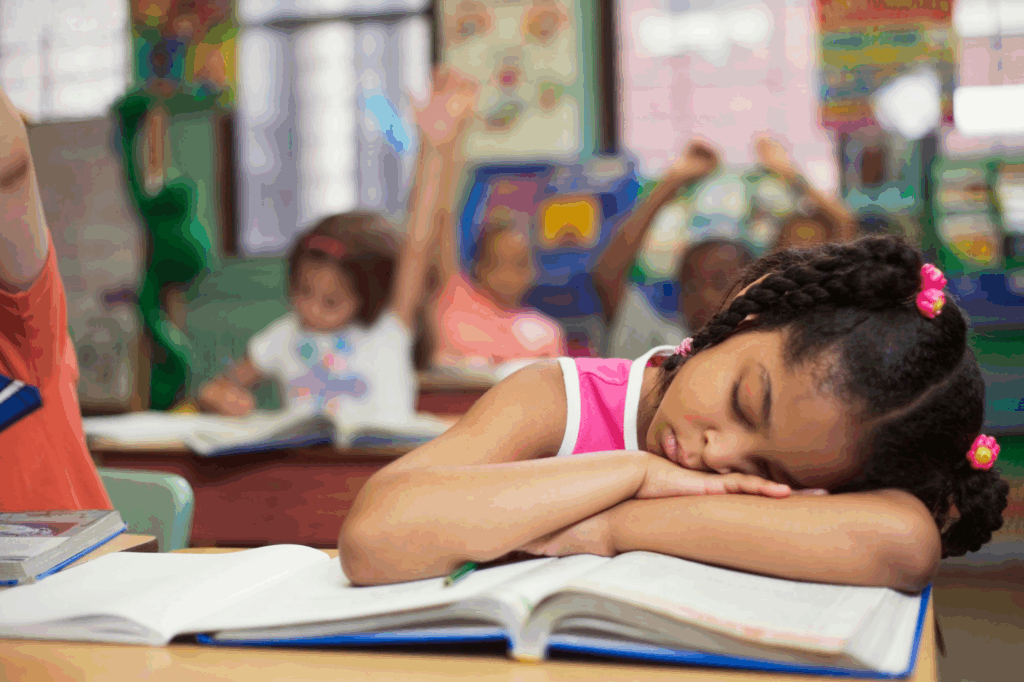

Studies show that individuals exposed to high-intensity, blue-enriched light during the day experience improved reaction times, task performance, and sustained attention (Viola et al., 2008). Commercial, government, medical, and educational institutions are rethinking the role of naturalistic light in building design and renovation. This is why lighting that provides adequate melanopic illumination is now being installed in workplaces, classrooms, and control centers to support alertness and productivity.

For those working indoors or remotely, installing circadian lighting systems like SkyView™ lamps and tile and maximizing natural light exposure during peak hours can make a measurable difference in energy levels and cognitive function.

Where to Enhance Blue-Sky Light Exposure (and Where Not To)

Because light is the dominant time cue for the circadian system, proper light placement and timing can enhance—or hinder—well-being (Lucas et al., 2014). When thinking about light exposure, its often useful to remember that for millions of years we lived by the sun’s cycle. You should have blue enriched light of the sun and sky (melanopic light) during the day and it should wane towards evening. The general rule for circadian light placement is:

- Use blue enriched light in areas of high activity—offices, kitchens, gyms—during the day.

- Use blue enriched lighting in areas that are not immediately near windows. If you can’t see the sky in your view, chances are you are getting less natural melanopic light than you need.

- Avoid white and blue-enriched light in the evening, especially in bedrooms and relaxation spaces.

- Bedroom lighting should be able to switch completely off or have a deep red nightlight setting to prevent melatonin suppression. Other sources of light during sleep should be blocked.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Circadian Rhythm and Health:

How does our circadian rhythm affect our sleep?

Our circadian rhythm regulates the production of the hormone melatonin, which is responsible for causing us to feel drowsy and in turn sleep.

Why is our circadian rhythm often referred to as our biological clock?

It’s a natural, internal timekeeping system that controls our cell, tissue, and organ functions by following an almost 24-hour cycle just like a clock and is synchronized by environmental cues, primarily light.

Can disruption to my circadian rhythm really affect my health?

Yes, as our circadian rhythm regulates and governs numerous biological and hormonal processes within our bodies, chronic circadian misalignment is linked to chronic inflammation, metabolic disorders, depression, cognitive impairment, and increased disease risk.

Can circadian disruption cause obesity?

Yes, extensive research now suggests a strong connection between chronic circadian disruption, inflammation and metabolic shifts that result in weight gain.

Can circadian disruption affect my immune system?

Yes, circadian rhythms govern our bodies at a cellular level. Research shows that immune system function is highly vulnerable to circadian disruption, that can contribute to chronic inflammation, disease risk, immune dysfunction, and general immune depression.

What can I do to improve my circadian rhythm?

Evaluating and optimizing proper light exposure so you get the right color spectra at the right time of day is one of the easiest ways to improve your health since light directly affects our circadian biology.

What lighting should I use at night for better sleep?

Amber or red light in the evening reduces melatonin suppression, promoting better sleep onset and quality. Remember, red lights don’t induce sleep, they just don’t provide the blue light that disrupts sleep. It’s the absence of blue light that is needed, not the presence of red light.

References

Brainard GC, Hanifin JP, Greeson JM, Byrne B, Glickman G, Gerner E, Rollag MD. Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001 Aug 15;21(16):6405-12.

Brown TM, Brainard GC, Cajochen C, Czeisler CA, Hanifin JP, Lockley SW, Lucas RJ, Münch M, O’Hagan JB, Peirson SN, Price LL. Recommendations for daytime, evening, and nighttime indoor light exposure to best support physiology, sleep, and wakefulness in healthy adults. PLoS biology. 2022 Mar 17;20(3):e3001571.

Buijs, R. M., et al. (2003). The suprachiasmatic nucleus and circadian control of the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 18(2), 157–166.

Chang AM, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015 Jan 27;112(4):1232-7.

Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, Ronda JM, Silva EJ, Allan JS, Emens JS, Dijk DJ. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999 Jun 25;284(5423):2177-81.

Figueiro MG, Wood B, Plitnick B, Rea MS. The impact of light from computer monitors on melatonin levels in college students. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 2011 Jan 1;32(2):158-63. Fishbein AB, Knutson KL, Zee PC. Circadian disruption and human health. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2021 Oct 7;131(19).

Grandner MA. Sleep, health, and society. Sleep medicine clinics. 2022 Jun 1;17(2):117-39.

Lam, R. W., et al. (2006). The efficacy of bright light treatment for seasonal affective disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 36(6), 863–873.